By Bill W, From the Grapevine book AA Today, published on the occasion of AA’s twenty-fifth anniversary in November 1972

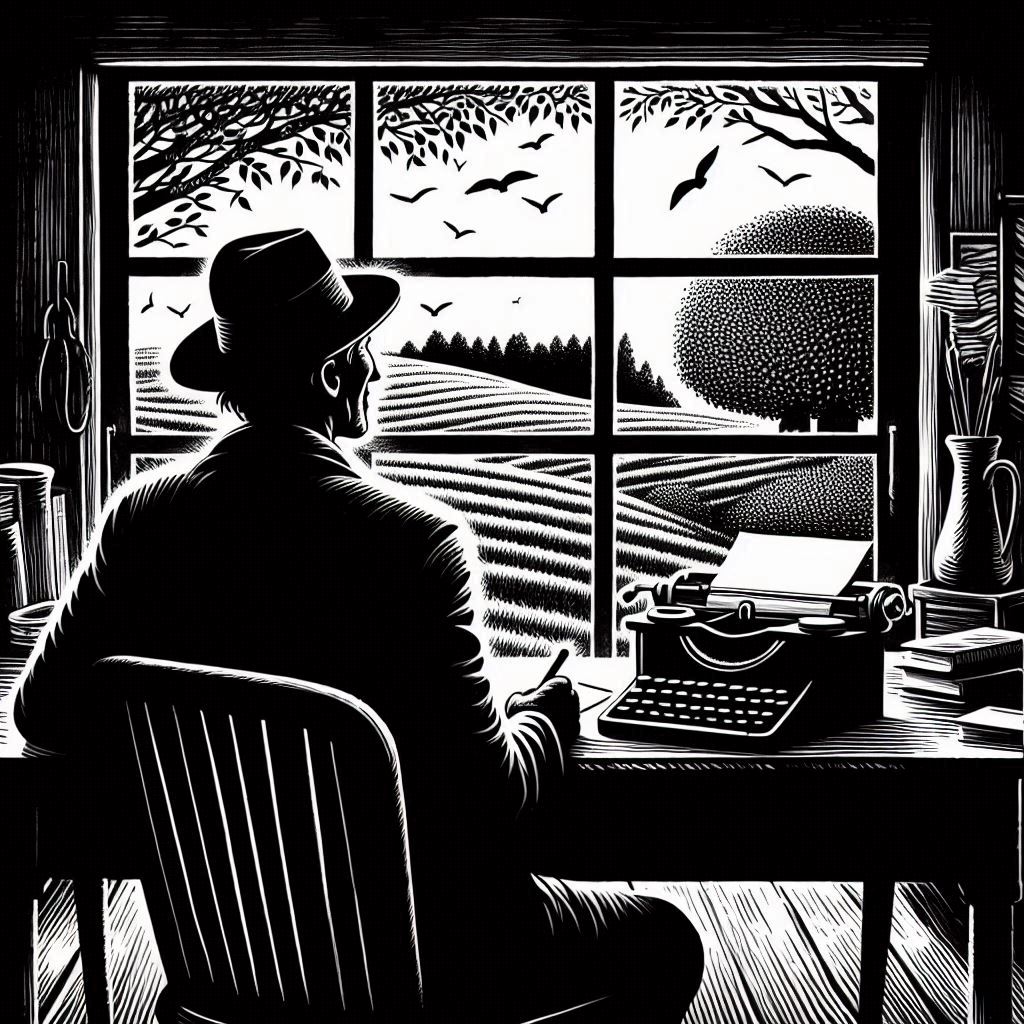

My workshop stands on a hill back of our home. Looking over the valley, I see the village community house where our local group meets. Beyond the circle of my horizon lies the one world of AA: eight thousand groups, a quar ter of a million of us.* How in twenty-five years did AA get the way it is? And where are we going from here?

Often, I sense the deep meaning of the phenomenon of Alcoholics Anonymous, but I cannot begin to fathom it. Why, for instance, at this particular point in history has God chosen to communicate His healing grace to so many of us? Who can say what this communication actu ally is — so mysterious and yet so practical? We can only partly realize what we have received and what it has meant to each of us.

It occurs to me that every aspect of this global unfoldment can be related to a single crucial word. The word is communication. There has been a lifesaving communication among ourselves, with the world around us, and with God. From the beginning, communication in AA has been no ordinary transmission of helpful ideas and attitudes. It has been unusual and sometimes unique. Because of our kinship in suffering, and because our common means of deliverance are effective for ourselves only when constantly carried to others, our channels of contact have always been charged with the language of the heart. And what is that? Let’s see if I can communicate to you something of what it means to me.

At once, I think of my own doc tor, William Duncan Silkworth, and how he ministered to me with the language of the heart during the last shattering years of my alcoholism. Love was his magic, and with it he accomplished this wonder: He con veyed to the foggy mind of the drunk that here was a human being who understood, and who cared without limit. He was one who would gladly walk the extra mile with us, and if necessary (as it often was), even the last mile of all. At that time he had already tried to help over twenty thousand drunks, and He had developed some ideas of his own about what ailed drunks: They had an obsession to drink, a veritable and a destructive lunacy. Observing that their bodies could no longer tolerate alcohol, he spoke of this as an allergy. Their obsession made them drink, and their allergy was the guarantee that they would go mad or die if they kept it up. Here, in contemporary terms, was the age-old dilemma of the alcoholic. Total abstinence, he knew, was the only solution. But how to attain that? If only he could understand them more and identify with them better, then his educational message could perhaps reach into those strange caverns of the mind where the blind compulsion to drink was entrenched.

So the little doctor who loved drunks worked on, always in hope that the very next case might some how reveal more of the answer. Read the full article